Jessica Hutchings

interview with Philip McKibbin

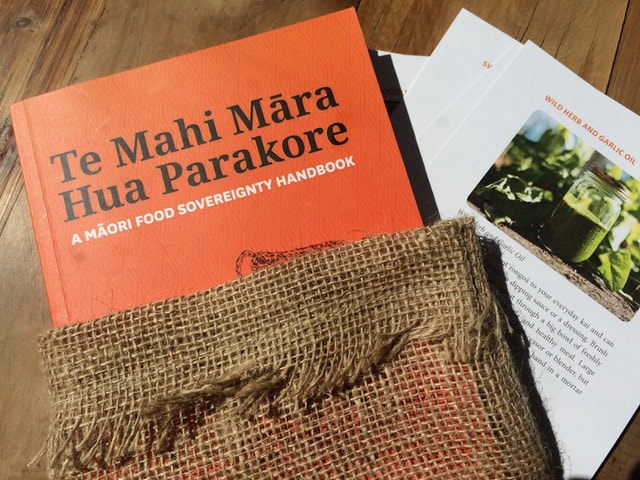

Dr Jessica Hutchings (Ngāi Tahu, Gujurati) is a hua parakore gardener and kaupapa Māori researcher. She is skilled in biodymanics, and is a devotee and teacher of Ashtanga Yoga. She helps steer Te Waka Kai Ora, the National Māori Organics Authority of Aotearoa, an organisation committed to environmental and cultural sustainability. Her book Te Mahi Māra Hua Parakore: A Food Sovereignty Handbook explores the practice of ensuring food-secure futures for whānau, and incorporates kōrero with other hua parakore growers.

|

Tell me about your hua parakore practice at Papawhakaritorito.

Well, I think the first thing for us is about our standpoint on the whenua. My wife and I are not from Rangitāne, Kahungunu, Te Āti Awa – ngā iwi o tēnei rohe – so being really clear that we’re manuhiri on this whenua is a really important starting-point for us. Our kaupapa is to tiaki the whenua, but we don’t hold that mana whenua relationship. I came to this piece of land through a little ad in the Capital Times – I’d been looking to buy a piece of land for quite a while – and walking onto other people’s whenua is a really interesting thing when you look to buy land in a Western property system. We came out here – we’re only 45 minutes north of Wellington – and it just felt right. I had been working with some of the iwi from around the rohe, and so just having a chat with a few people that I knew about the whenua, and letting them know our intentions, and then that was an opportunity to learn a bit more about the cultural history of the maunga all around us. That’s the back of the Ōrongorongo, and there’s a lot of kōiwi up there, and so it was really important to have that kōrero before we came onto the whenua.

|

That was a starting-point, and then the hua parakore really came onto the land because I’d been involved with Te Waka Kai Ora, the National Māori Organics Group, for a really long time. They were established in 2001, as there was a call for Māori organic producers to have a kaupapa Māori verification system for organics or what we call Hua Parakore – Māori organics. There are four organic certification systems in Aotearoa, and not one of them provides any opportunity to tell a kaupapa Māori story about food production by Māori growers. With my research hat on, as I am a trained kaupapa Māori researcher and a recovering academic, we applied to the then Foundation for Research Science and Technology and won a substantial research grant to undertake a three-year kaupapa Māori research project that connected Māori growers with rongoā practitioners, with people in export markets, with certification standards-setting organic peoples, and we built the Hua Parakore framework.

Initially, we thought this might have potential for an export market, but the uptake’s really been amongst whānau and in building whānau food-secure futures. So it’s really been a way, through the six kaupapa – Mana, Wairua, Māramatanga, Te Ao Tūroa, Mauri, and Whakapapa – to be able to express ourselves through kaupapa Māori in describing what we do and how we do it.

I also practice biodynamics on the farm, and it’s really similar, for me, with Hua Parakore, as it’s about vibration, it’s about energy, it’s about land healing. I have had a kaupapa on the farm in the past of being slaughter-free. However, in biodynamics we do use animal parts in the making of the preparations, and within this process there is a process to honour the beast and use animal parts with a real reverence. So it is about having that reverence for the beast, the noble beast, of the animal and the cow, the horns and the hooves, and the relationship and the connectivity between when the hoof of a cow who stands on the Earth, stands on Papa, whose horns reach up to Ranginui, out to the Stars and the Cosmos. There’s a polarity that is brought onto the whenua when you connect with the animal – and in most cases in biodynamics, it’s the animal manure, the cow dung, that you’re working with, which is really that in-between space, between the hooves on the ground and connecting to Papa and the horns reaching up. You think of the digestive system of the cow; it’s really that middle space, that space in between that can help to bring balance when you use cow manure in a certain way on the whenua. It brings about healing, and it brings about balance. It’s about that balance between Earth and Sky energy. So that’s a biodynamics kōrero, but it’s also a Hua Parakore kōrero, cos for me it is about mediating that relationship between Rangi and Papa, between Stars and Sky and Earth.

So, we’re Hua Parakore verified, we did have full organic certification with Organic Farm NZ which cost about $500 a year. You’ve got a random Pākehā man who turns up once a year to do the verifications for you, you’ve got no relationship, there’s no whanaungatanga, it’s very ‘fill out a form and tick the box’ – whereas the Hua Parakore system is really relational. It’s about making connections with other Māori organic growers or whānau or people within the community, and then they end up becoming the verifiers. So it’s the third-party verification system, which is what you’d call it in international standards settings. Organics and parakore is about the integrity of the land and the system, but it’s actually about the integrity of the product, as well. It is that connection all the way through the food system – the food from the land, and then the food that we eat, and having that connection.

I suppose now that we’ve been Hua Parakore certified since 2011 – so eight years – and we were organically verified for about four or five years before that – I’ve since dropped that Pākehā certification – Hua Parakore is just our way of life, now, on the farm. And that’s for lots of whānau that I meet, living on papa kāinga, or on whenua, or even in the suburbs. It’s just about a manifestation of expressing kaupapa and bringing that back. It is about healing work. I teach yoga as well, and yoga is also about healing, and then I come onto the land, and our work on the farm is about land healing and of course food is also about healing. When we work on the edges in a colonised country that’s right in the midst of everything – not just nationally, but globally – we have to balance that out with being able to do some healing work. What I like about the Hua Parakore is that it’s able to shift over time, so maybe it wasn’t so much about healing work for me five or six years ago, but now that’s just really prominent.

I think having all those years of putting biodynamic preparations on the whenua, you really start to feel that things are actually changing under the ground and in the soil, and you’re seeing more clover and more aeration, the worm count is higher, and you’re bringing life and biodiversity back onto the land and in the soil. And that’s a kaupapa that fits with Hua Parakore as well: soil sovereignty and the notion of rebuilding healthy soils again. You know, people talk about food, ‘Oh, I want to grow food. How do I grow food?’, and my first response is, ‘Well, you’ve got to grow soil.’ And that’s what biodymanics and Hua Parakore practices do. It’s about enhancing the mauri, enhancing the microbiology, enhancing the nematodes, and all the other good things that are in there, through the practice of making compost. I think compost is a little bit like baking or cooking - you’ve just got to get all the ingredients right and have a relationship with them, and then you take that relationship through the compost onto the land and into the soil, and then into the food. It’s a natural ecosystem, a natural loop.

How has your Māori and Indian whakapapa influenced the way you think about kai?

In so many ways. I’m adopted, and so it’s my birth mother’s side that’s Indian, and she’s from – or, we’re from – Gujurat. I’ve been back to the village and seen the village life, and it feels like, in lots of ways, that it’s in my bones. Really subsistence life: in the morning, past the front of the house, people are walking with the harvest for the day or off into the fields and the paddocks, and it’s very real. It’s like, ‘We have to go to work, and we have to work for the food. We have to tend to the land in order to be able to eat tonight.’ And there’s something about that simplicity, and that honesty, and truth in that, that has integrity, and that very much resonates with kaupapa Māori and standing in that integrity as a Māori Indian woman on the whenua producing kai.

I’ve been really lucky over the last 20 years to have made a lot of food connections with some amazing farmers and activists in India, including one of my sheroes, Vandana Shiva, who is part of the group Navdanya, which is a seed saver movement along with groups like Diverse Women For Diversity. I have learnt from these connections about the importance of seed diversity and the importance of ensuring diversity within seed stock. It is important to retain not only in our seed source, but also the ecological knowledge as well. It’s one thing to save seeds and say, ‘Now I’ve got a seed bank,’ but have you got that diversity, that intergenerational diversity in your community to hold that knowledge and to keep passing it down?’ And 20 years ago, when I was starting to hear all that kōrero, it just blew me away – about the role that women played in traditional communities, subsistent communities, indigenous communities, for being knowledge holders of seeds, plants, foraging, and it made me think, ‘I didn’t grow up with any of that.’ That’s all been learnt, so I’ve been really drawn to the politics that continues to come out of India, particularly in the ‘70s with the fight against the Green Revolution, the mass farmer suicides that have happened in India because of the introduction of pesticides and genetic engineering, and the impact of mass patented agriculture on farmer livelihoods. You plant one crop of GE cotton, Bt cotton, and then you’re in this vicious loop of needing to buy pesticides and the fertilisers to keep the ground fertile, and then you’re locked in through an economic model that is absolutely corrupt, and then you’re having to purchase those seeds again because they don’t self-germinate. There is something incredibly violent about modern agriculture that is a fracture in the natural rhythm of life.

|

My grandfather was one of the many hundreds of Indian men that was imprisoned when they fled with Gandhi across the plains of Gujurat. Gandhi defied British rule when the British decided to put a tax on salt – basically, claim ownership of it – defied British rule and picked up a handful of salt, and that led the march of many peoples across Gujurat who were actually fleeing the British who were after them. My grandfather was caught and imprisoned for a year, and it’s that connection to passive resistance. And in lots of ways, food growing, seed saving, food knowledge building, is a very gentle form of resistance. It’s hard to explain it; it’s just something that you do, and I suppose it’s the approach and the way that you do it. It’s different from sitting on a combine harvester in the Dust Bowl of America, thrashing the land to try and get something out of it. It’s almost like we’re going back to being nature beings, and we are the land. So we’re working with it in a way where, if we’re caring for ourselves, we want to care for the whenua as well.

|

What impact has colonisation had on traditional Māori plant crops?

I think we’ve lost a lot of knowledge. First of all, our land’s been taken, so we’ve lost our ability to connect with our whenua. The most productive pieces of land in New Zealand are not owned by Māori; they were confiscated and stolen. We often talk about marginal, multiply-owned Māori land. We’ve been left with the least-productive growing areas. So I think that’s really interesting when thinking about Māori plant crops and food secure systems for whānau.

Where do you start? Colonisation, agriculture. I think it’s about the food system, really – the impact of colonisation on the whole food system. Percy Tipene, Founder of Te Waka Kai Ora, used to talk about how our puku is really colonised, and that we’ve lost the ability to eat. I know my son wouldn’t eat lots of the traditional fermented foods, or things like that. I don’t think he could down a kina, but his father could; he’s from a different generation that is very urbanised and disconnected from his mahinga kai or taonga kai. In the everyday, we have to enter a colonised food system in Aotearoa just through the purchasing of kai that is driven by a capitalist system.

Māori food sovereignty for me is about returning to eat the landscapes which we’re from. It doesn’t matter to me that on our little farm I’m growing European vegetables along with some kai Māori; it is really about returning to eat this landscape because I’m growing the soil on this land, I’m tending it, I’ve got a relationship with it, I’m nurturing the animals that provide the manure to make things grow. So I think it’s really about that type of connection. Whereas our current food system such as the experience we have when we walk into Pak‘nSave, we’ve got absolutely no relationship with the whenua or the growers, and we have to buy it in plastic – what the parakore movement term ‘colonial waste’. So having an analysis around that. And there’s a privilege with this – there’s a class privilege with this – to be able to have an analysis. A lot of our whānau don’t even have enough pūtea to feed everybody in the household in the everyday, so there is a privilege with that, and what do you do with that privilege? For me, I have to think about, What’s the marae that’s closest to me? Where are the food banks? How can I help? If we’ve got surplus, where do I share it? It is this practice of manaakitanga, to elevate the mana of whānau, so you have to bring that into play as well.

But our food system is broken. I speak on behalf of Te Waka Kai Ora, and we’re advocating for food systems that are diverse, that are based on collectivism, that are about regenerative economies, about biodiversity, that are about parakore – so, they’re about waste reduction, closed-loop systems. On our little farm, we basically generate everything we need to do everything. So, getting firewood today, which is just all the gorse that’s on the ground that’s all dead. The manure comes from the cows that are on the farm. We’ve got nitrogen – green stuff – for putting in the compost. We cut hay, so there’s your carbon. Food, saving seeds, so we don’t really need to go off and buy things. This notion of impact of colonisation on agriculture, there’s a big unlearning that we need to do, but it’s sensory as well. It’s every part of us that needs to be undone around our relationship with food. It’s a big journey – it’s a life practice, because it’s seasonal, and sometimes this time of the year – I was just saying to my partner earlier this morning, as it’s spring and there’s so many weeds around, but actually, it doesn’t really matter, because they can all just cycle around, we can just let everything go to seed this year and not do anything, and it’ll all just cycle around for next year. And that’s not a bad thing – that’s not a bad thing to not be in control of the agriculture, but to be a part of it. And I think that’s a really important distinction in Hua Parakore agriculture. It’s that, actually, we are a part of it, we are it. Is there any separation? There’s no separation, really, from it – we are nature, nature is us.

What is Māori food sovereignty, and how do our practices around kai relate to tino rangatiratanga?

Māori food sovereignty is about food-secure futures for whānau. It is about returning to eat our cultural landscapes in ways that ignite our kaupapa Māori sensory faculties, in all aspects of ourselves. In terms of exercising tino rangatiratanga around food, first up for me would be to have a relationship with the food. So, Where did it come from? How did it get there? Who grew it? Where’s the seed from? Are we eating in community? How are we eating? And this is where Ayurveda and my Indian side jumps in, because it’s about that mindfulness in eating, bringing conscious awareness to eating and how we’re eating. I was at a hākari recently, and it was just beautiful, all this beautiful hākari kai on the table, and it was a big, buzzy hui, about 150-200 people there, but you get to the table – and this is not a comment on manaakitanga or anything, it’s more a comment on conscious eating – you get to the table, so many people, we’re all squishied up, and I know there would have been karakia before we went into the wharekai, but then it’s just like the Vikings, you know? It’s like we’re eating mindlessly, and just hoeing into all this food.

I’ve studied some Ayurveda, and what I like about that is, actually, you don’t talk when you’re eating. We chew 20 times for one mouthful, and that gives us an opportunity to create the digestive juices to prepare the body for the food that we’re about to ingest. And within that process, you’re connecting with the consciousness, eating in a different way. It’s part of slowing down in the world, really. Food growing is so slow, and maybe we should just be eating a lot more slower. I think that would be a start for tino rangatiratanga; it might give us an opportunity to have a bit of reflection. Of course there are other areas of relevance such as interfacing with the government, national and international neoliberal policies, the Wai 262, and being advocates in Treaty processes, and ensuring that the Convention on Biological Diversity is upheld, along with Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights being protected – but to be honest I just wanna come back and be on the farm and do the healing work with the land.

There are a lot of awesome people who are doing amazing resistance work. Ngāti Porou and the Coasties who have been out on the boats protesting about fracking and oil exploration is a really big expression of tino rangatiratanga in our food system. Our whole food system is based on oil; we need oil for everything in the modern-day food system. And if you say that, you make the link to ‘the food system’s broken,’ because we understand the impact that an oil-dependent economy is having globally on the environment and on the Earth’s ecosystems.

You take care around the whakapapa of the seeds you plant. Why is this important to you?

Seed saving’s really important. There’s something like five or six multinational companies that own about 95% of the world’s seed stock. We’re very limited in the diversity that’s available in the supermarket – wheat and corn, basically. Diversity’s important for so many reasons. It’s important in our ecosystem, because that’s how our ecosystems survive. It builds resilience when you’ve got diversity in there, so growing monocultures like they did in the Green Revolution in the ‘70s is just a complete failure, and they introduced all of these pests and bugs and weeds – changed the ecosystem, put it out of balance. So diversity through having a diverse seed stock and then being able to plant diversity on the land is really important.

For us, diversity comes with the ngahere – and we’re surrounded by it out here – is a really big, integral part of the actual food growing of celery and lettuces and this, that, and the other, because the fungi from the native trees is like this web that reaches out across the whole whenua; it’s all connected. There is no boundary between my food growing practices and the native trees that are planted around the house, and then the paddock with the BD preps on it, and then the bush life. Actually, it’s this seamless ecosystem under the soil that’s all connected up, and that’s really diverse, that’s about diversity under the soil. If you think about that under the soil, we need that on top of the ground as well, and we need that for the health in our digestive system in our bodies. I’ve got a book coming out, hopefully in Matariki next year, on soil sovereignty, exploring some of these ideas a little bit more, trying to bring a focus into the soil. Everyone’s so obsessed with growing food above the land. But what about the soil? We’ve got to start with that relationship in the soil.

Talk about the abundance of nature, my gosh! What, you plant one seed, and then, at the end of the cycle of that planting, it goes to seed and then you’ve got 1,000-2,000 seeds that you can share out from that one seed. I can’t believe that we’ve got this mentality that we’ve got to pump the land with fertilisers and pesticides, because there’s just that abundance anyway within nature. The other thing about seeds is the potential that it holds. Seeds can lie dormant for a long time but yet still hold that potential. We just planted some seeds that had been sitting around for about six years, and I just can’t believe that they germinated, and that now they’re up and away. It’s almost like a holder of knowledge; it’s a holder of energy.

There’s a lot of vibrational energy every day to be held in a seed, that then that plant does the end of its cycle, the seed drops back down, grows again. So you’ve got this continuous flow of light energy within that seed, that it’s held. This is why I think that coming back to sensory knowing is really important. Cos we might not know it intellectually, but we have this real intuition, if we can connect back to being nature beings, of knowing that we need to caretake for that and what’s the best way to do it, and maybe the best way to do it is to do nothing and to leave it alone.

It’s a global concern that I have. I am really concerned about the future of food. And having done some recent research work with some Māori agribusinesses and farming communities, it’s very much driven by kaitiaki values, but a lot of our Māori agribusiness industries are driven by shareholder dividends. So we need to take profit, and we need to take money out of food, because food is nature, and so we need to think about alternative productivity paradigms that value food not as a commodity, but as sustenance and nourishment – we need to flip our values system round with food.

I’m concerned with the way that global capital circulates. How do you even start to address this, apart from at a local level of doing things? The way that it circulates, it re-inscribes the multinational relationships and economy between corporates and our food system, and all that’s driving that is food-as-a-commodity and food-as-profit. I mean, we even talk about the commodities market. Since when did something that indigenous peoples lived with for centuries and thousands of years become a commodity? It’s something to be in reverence of, connected to and a part of.

|

Our food policy regulations in New Zealand are not up to scratch. I think we should have GE labelling on everything. I don’t think if it’s only got so much percentage, or if it could be potentially contaminated – I don’t think that’s good enough. I want to know everything that I’m eating. I don’t want to buy food in plastic packaging. And I also, too, think that we really run a risk of increasing non-communicable diseases if we don’t start bringing diversity back into the food system. Nothing in the modern food system lines our gut or grows bacteria in the way we need to grow our gut bacteria, just like we need to grow microbiology in the soil – it’s the same type of crisis, really. It’s just being mirrored under the Earth and on top of the Earth with us standing here as human beings.

I don’t see any spaces for Māori to participate in the development of the food system here in New Zealand. Who’s setting food policy? Who’s regulating it? Why aren’t we at the table? We’re advocating for change, but we’re not even at the table. I don’t even know if the table’s functioning. I don’t even know what table it is. Who’s doing food policy? We don’t seem to have a very transparent food policy system in New Zealand, and it’s not very connected with tangata whenua – let alone all New Zealanders.

|

We have our own food system model. We’ve just been developing a Kai Ora food system model, and this brings a kaupapa Māori into thinking about food systems in New Zealand. I’d like to get to the policy table; I’d like to get to the leadership table; I’d like to get to the decision-making table about food systems. I’m really concerned about the continual non-funding of organics in New Zealand, let alone Māori organics. In my travels overseas to international organics conferences, I hear farmers from the EU and from North America and Canada, almost with hope, ask why New Zealand has not been a beacon to save the world’s seeds. We’re an island nation, we can be free from GE contamination – pretty much – whereas in Europe, it’s pretty much all over up there, and in North America it’s way over, and in Canada it’s way over. I mean, how do you stop GE contaminated seeds blowing over into an organic farmer’s farm? We have the potential to be an organic seed lifeboat, and I think the world is really, really going to need that. And I’m not talking about that project which is locking them all away under ice sheets for the future, but actually to save seeds and share them outside of the commodity-driven market with the rest of the world, so that we can bring diversity back into our food system.

Tell me about the animals that inhabit Papawhakaritorito.

You’re interested in everything! (laughs) Well, it all starts with the worm, doesn’t it? All the nematodes and everything under the ground. I think we’re gonna turn some compost this afternoon, and I’m looking forward to meeting all those little critters that are in there. I have a real care for those beings. I really like it when I do a spade dig in the paddock, and there’s more worms per spade dig than there have been in the past, and the soil’s nice and aerated, because the big fat worms have been going through it and stuff.

Lots of bird life - full of kererū and tūī at the moment with all the natives in flower, and yeah, it’s just native birds all around us. And then we’ve got fish life, as we’ve got a beautiful river that runs through the farm, it’s called the Pākuratahi River. We’ve got lots of trout in the river, and lots of tuna. We’ve got a lovely community with Pākehā neighbours out here, and I’ve put down a net with them and shared food, and we see what we can gather from the river.

|

I’ve got a dog. Her name’s Tahi. We haven’t got many animals. We’ve just got two goats. We fenced off a paddock last year that had lots of gorse and broom in them, so the goats are our little organic weed munchers for that. And I have had a family flock of sheep– I was up to about 25 – Romney-Perendale cross. But when you have a slaughter-free farm, you have to do something with all of those babies when they get really old and a bit geriatric. I’ve recently been picking up sheep from the paddock who’ve been keeling over, and I did actually get the farmer in from next door to dispatch three of them recently, just because it felt like that was more humane than letting them hobble around. Sheep lose their teeth as they get older; they wear down – they haven’t got a mouth full of teeth like humans – and then they can’t actually eat. So that was an interesting decision, and now I’m only left with two, and a whole lot of grass that I’m sharing with my neighbour, as I’m not quite sure what the next step is for animals and caring for them and what we want.

|

I have had a cow, and she came to us and calved. In biodynamics, a lactating cow with horns is just primo cow poo, so that was good. But that was a big learning, as cows are herd animals, and she came from a dairy herd, and unless you raise a cow from a calf to be by itself – you know, that notion of a house cow – if you’re taking a cow that’s spent all of its life in a dairy herd out of that herd to come onto a farm… She just wasn’t very happy. So I asked my neighbour if she could graze with his cows, as she needed friends, she needed to be in a herd. It is important to understand what the animals need.

We’ve got too many rabbits, and a lot of pūkeko. Animals in a hua parakore and a biodynamic system are really integral. We initially got sheep, as they’ve got golden hooves – they don’t put a lot of pressure on the land, so they don’t compact it down. So that was the choice around getting sheep.

Papawhakaritorito has been a slaughter-free farm. Why is animal welfare an important part of your tikanga?

Well, it’s that manaakitanga and that ethic of care. I learnt in biodynamics about really having reverence for the beast, honouring the beast, and it really changed things for me. I’ve been a vegetarian for a long time, but I’m not anymore.

With biodynamics, in the preparations we use the cow dung, but we also use the mesentery. We use the brain; the whole head of the cow ends up being submersed in a bucket to make oak bark preparation that you use in composting. They use the horns. So there’s different animal parts that are used in biodynamics to make the preparations, and when I did that course, I actually had to sit out for one of the preparations, as it was quite raw. We had seen these cows in the paddock, and then they were off to be slaughtered. The body went to the abattoirs, but all of the other body parts of the cow were brought back, the bits that we needed to make the preparations, and it just felt quite confronting. But what I understand – Rudolf Steiner had a reverence for the beast; it wasn’t mindlessness – in some ways, it was done in a very mindful way. There are lots of lovely songs in biodynamics about honouring the animal. There was a real understanding about the offering that the animal could provide, in terms of what it could give, and so I probably would think about it in that way. So I don’t grapple with that anymore. I buy our preparations from the Biodynamic Association, and I know those animals are cared for and loved in the most beautiful way, and honoured for what they can keep giving – I mean, really loved up. There’s a beautiful Hua Parakore organic dairy farmer, Cathy Tait-Jamieson in the Manawatū, and she used to do biodynamics, and all of her cows are just so loved up. It’s that thing, How are we treating another sentient being? What’s our relationship to that sentient being? And there is a real sentience in the relationship in biodynamics between the human and the beast.

I have loved watching a flock of sheep age, and I have loved keeping a family flock together. And I’ve liked keeping the tails on. Can you imagine if your tail got cut off?! I mean, we only cut the tails because humans don’t want dags and they get mucky around the bum, but really it’s fine. It just means we have to look after them in a different way. So it’s nice to have animals in their absolute, most natural state.

You use innovative techniques to deter animals like rabbits and aphids from your māra. I'd love to hear about those.

I do lots of companion planting in the māra. These are plants that share a beneficial relationship, such as planting marigolds with the vegetables to bring in beneficial insects.

It’s like Watership Down out here at the moment. It’s terrible. So I’m not very good at deterring rabbits. I don’t know how you deter rabbits. We’ve done nothing, really – I mean, they’re everywhere. We drove into the paddock today, and there were literally 30 that ran out across the road. I think they’re a part of the ecosystem in some ways. I mean, I’m not farming for profit; I’m on a piece of land to bring it back to life. If that means rabbits want to come here, well, that’s alright, as long as they don’t get into the garden up at the house, and they don’t at the moment. We built a polytunnel a couple of years ago. I was having a lot of issues with pūkeko, rabbits – you know, everything was in the food. And now I’ve got an indoor growing tunnel, cos I’m not in a great climate where I am. I’m not in the Far North of the Hawke’s Bay, so it’s a short growing season. So that’s really changed up growing, being able to grow indoors.

How else do we deter things? We’ve never put a trap out for a possum. We’re not very good. Yeah, I don’t think I’d want to deal with an animal in a trap – at all. I don’t know. Talk to me in 10 years, I might be drowning in rabbits!

Interviewed: October, 2019

Published: December, 2019

Published: December, 2019