Kayla Howard

interview with Philip McKibbin

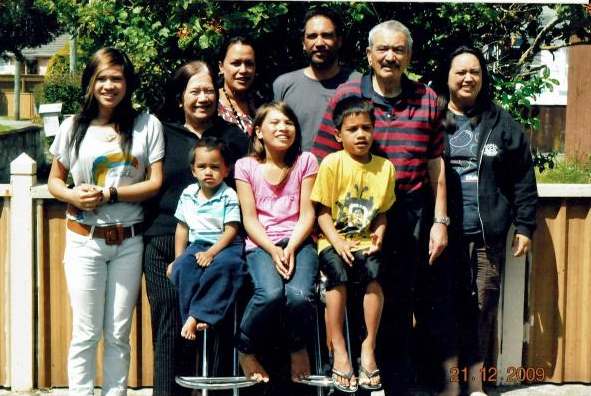

Kayla Howard (Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Kahungunu) is an animal rights activist. She is studying te reo Māori at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. She and her adorable dog, Bear, live in Te Whanganui-a-Tara.

Who has had the biggest influence on the way you see the world?

|

Definitely my grandparents and my parents, and of course my dog, Bear, growing up. Yeah!

I was quite lucky, cos my granddad looked after me after school, so he had a lot to do with me while I was young, and he taught me manaakitanga, how to care for people, and he was just quite a peaceful guy as well, as well as my nana, she was very loving. And my parents, I think they just taught me how to be open-minded and think critically. Also, I think that they were in the generation where they started to think more about their own culture, like being Māori and their identity. So I was quite lucky, cos they fed me those values of having an identity, in terms of being Māori.

When I was six years old, for my birthday Mum gifted me a dog, cos I’d always wanted one. I’m 20 now, and he’s still alive, and he’s been my best friend ever since. So I grew up with a close relationship with animals, and that definitely helped with my transition to veganism. It was quite easy for me, cos I already had that connection with animals.

|

You're currently studying te reo Māori at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. Ka rawe! Why is te reo rangatira important to you?

It’s definitely back to the identity thing. When I’m speaking te reo, I feel like I’m at home with the language. It’s quite different, isn’t it? You’re just in another world when you’re speaking your own language. I was quite lucky, cos I grew up going to kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa; but I left kura when I was about eight, and went to mainstream school. My family moved to Australia. We came back a year later, but I didn’t go back to kura kaupapa - so I kind of lost that connection, and I also lost my reo. That was tough, but I was lucky, cos I had my dad who speaks fluent, so I didn’t completely lose it. Now I’m living with my dad, and it’s been a lot better, cos I’ve been more exposed to te reo, and it’s definitely improved, just in the year. I think te reo is very important. It’s important to hold the language.

Tell me about your transition to veganism.

In January 2016, I went vegan. It was at the time I went on holiday to Australia, when I was staying with my sister. She was vegetarian at the time - she’s still vegetarian. And I guess that being around someone who was vegetarian just made me a bit more curious as to why she was, and trying to understand more about why she went vegetarian, cos it just seemed a bit weird to me. (laughs) So she told me, ‘If you want to know more, then you should watch Earthlings,’ cos I was really wanting to understand why. Earthlings is a documentary based on what happens inside factory farms, and they show all the different ways of how they kill animals. It’s just very - not good. And then as soon as I watched Earthlings, it just - yeah. (laughs) It’s horrible, and I was like, ‘No, I can’t do this anymore.’ And just at the moment, I thought, ‘I have to go vegetarian, and then vegan.’ I went straight to being vegan, actually.

I have to say, it was easy for me, because just by watching how extreme animals were treated, it just made me feel so angry, and my willpower was a lot stronger than the inconvenience of going vegan.

You've been involved in lots of protests. Why do you engage in this form of action?

Definitely one thing is, I feel it’s a way of me trying to help as much as I can, because being vegan is definitely great, but I know there’s still much more I can do. It helps me feel empowered, but I also know that by doing this I’m helping to share that message with people. Cos just like my sister was vegetarian, if she wasn’t vegetarian I wouldn’t ever have gone vegan. So just being exposed to that is, yeah, quite powerful.

I’ve been to the animal rights march in Auckland, and that was really cool. And I’ve been to some of the Cube of Truths held in Wellington. The Cube of Truth is street activism. We stand in a cube, and we show screens of what happens inside the factory farms in New Zealand. I think it’s a really good form of activism, because you don’t really force it on people. You get people who are interested in learning, and that, I think, is better than trying to push it on people, you know? And if they’re interested, the outreachers will go and talk to them. And the rodeo protests - there’s so many. The SAVE Movement, also in Wellington. Those are just a few. Oh, and protesting against animal testing at Victoria University.

Do you make connections between animal rights and tino rangatiratanga?

I definitely think there are a lot of things that both of them share. I think tino rangatiratanga and animal rights both strive for justice, and being free from oppression, and trying to take control, in a way - because animals have been forced to be in such a powerless position, and so have Māori, who have had their rights taken away and their land. So it’s about trying to get back that power again.

You've told me you view veganism as a way of decolonising our diets. How does that work?

When our land was confiscated, most of it was mainly used for farming animals, and clearing all of the land for farming. I see it as like, if we’re buying meat and dairy and eggs, we’re pretty much supporting those industries that confiscated our land to begin with. So for me, it’s like, if we eat more plant-based and don’t really support these animal industries, then I guess we’re not giving them more power. It’s a way of trying to gain back that power again.

I feel like that’s a big part of decolonisation, because it’s something we do every day. We have three meals a day, and it’s such an easy way to make a difference and make a stand. A lot of the time, we see these problems as things we don’t have control over, but when you look at veganism, you can be like, ‘I can make a difference to this, I can contribute.’ Being vegan helps so much!

The notion of tiakitanga, or kaitiakitanga, often comes up in connection to te taiao, to refer to the ways in which we relate to the natural environment - and how we might do better. It's connected to whakaaro around kai, and the harvesting not only of plants but of animals, like birds and tuna. Do you perceive a conflict between this traditional notion of tiakitanga and the modern idea of animal rights?

I think there’s definitely a strong connection between kaitiakitanga and veganism or modern animal rights, because they’re both based on the value of compassion. That to me is a really strong connection, or alignment.

There definitely is a conflict between the traditional notion of kaitiakitanga, because what we did back in the days was essential for our survival. We had to rely on other food sources, because we couldn’t just rely on plants to survive. So it wasn’t really possible to be fully plant-based or anything. But now, since the world’s changed so much and we have so much variety, it’s not really necessary to harvest birds or tuna for food to rely on.

This is a really hard question, cos I’m really conflicted by it too! (laughs) But I think if we base kaitiakitanga on the traditional way of following kaitiakitanga and applying it to now, when the world has changed so much, I don’t think that would work, because like we see all the time, tikanga always changes, and when the world changes, so does tikanga. So I think that kaitiakitanga doesn’t have to stay the same. We don’t have to follow every part of kaitiakitanga that doesn’t fit with our world today, cos we know that the bird populations and the tuna populations are probably best left being as rāhui, rather than still continuing to eat birds and stuff.

Rāhui just means where you make a place tapu - tapu meaning ‘restricted’ or ‘sacred’. A rāhui is usually placed on something because the population, or whatever, needs to be replenished. A lot of lakes are having rāhui put on so that people don’t fish from there or anything, or so humans can’t interfere, so it can replenish again, and be returned back to the natural state it once was.

What are your hopes for the future?

I’m not a future person, but I should be! (laughs) I think my hopes for the future is definitely, for myself, to be stronger in myself, in terms of being strong in my te reo Māori, being strong as a person, and also maybe gaining some skills so that I can hopefully influence people to help them think more consciously about what they eat as well as how they live. That to me is one of the biggest aspirations. In terms of career, I’m not too sure, but I really want to do something that’s of service to others - hopefully some sort of career in that way.

I definitely have faith in our generation. I think we are a lot more aware, maybe cos of social media. So I definitely think that our future generations will hopefully come up with lots of solutions and just think more critically, and be more aware and conscious, and have the values of compassion to make more of a difference and improve the world. That’s what I hope for future generations, for sure.

Interviewed: October, 2019

Published: December, 2019

Published: December, 2019