Laura O'Connell Rapira

interview with Philip McKibbin

|

Laura O'Connell Rapira (Te Ātiawa, Ngāpuhi, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Whakaue) is the Director of ActionStation, a social justice organisation. She is also on the Board of JustSpeak, a criminal justice movement. She lives with her partner in Te Whanganui-a-Tara.

Tell me about the social justice campaigns you've been working on recently.

|

In our team at ActionStation, we’re always working on or supporting up to 10 campaigns or kaupapa at a time, so it’s always busy. Our main focuses for the past few months have been:

I’m also on the board of JustSpeak, and one of their main focuses has been restoring the voting rights of people in prisons, which just experienced a win! So that’s awesome.

- supporting young and progressive independent candidates running for local government to get into power

- coordinating a powerful submission for healthy waterways and rivers made by 1,700 ActionStation members

- working with six other NGOs and 80 volunteers around the country to organise communities and drive the media agenda to call for an increase in income support and benefit levels as a key way to end poverty in Aotearoa

- supporting a coalition of Māori, Muslim, Pasifika and Pākehā people to oppose the militarisation of police

- calling for Oranga Tamariki to devolve power and resources to hapū, iwi and kaupapa Māori services for delivery of services relating to whānau and tamariki wellbeing

- supporting the School Strike 4 Climate marches

- turning our Tauiwi Tautoko training programme into an online course

I’m also on the board of JustSpeak, and one of their main focuses has been restoring the voting rights of people in prisons, which just experienced a win! So that’s awesome.

How did you become so passionate about social justice?

I didn’t grow up in a particularly political household, but my life has been profoundly shaped by the decisions that politicians have made. For the first seven or so years of my life, I grew up in a single-parent household, and it was during that time that Ruth Richardson ruthlessly slashed income support in what is known as the ‘mother of all budgets’. I lived in Māngere for the first three years of my life, then my Grandfather passed away when I was six, so my Mum and my Aunty combined their inheritance to buy the cheapest house in a flash neighbourhood called Laingholm. It’s in the Waitākere Ranges, past Titirangi toward Huia, and these days is full of million-dollar mansions. This meant I got to see the difference in opportunities and resources available to those in decile-nine areas compared to decile-one. It is also meant that I saw the difference in how heavily these areas were policed (or not) and all of those experiences have been really formative for me.

Like a lot of Māori, I also grew up not knowing how to speak my native tongue because of colonial laws and practices that took it away from my whānau three generations earlier, resulting in it not being handed on. That hunger inside me for my culture is politicising.

I’m also queer (bisexual), so that’s an additional identity that has been politicised by the Church and State and has likely made me political / led me to social justice.

What values guide you in your mahi?

Whakapapa. The long and never-ending line from the atua to the whenua to the ancestors to us. This value helps me feel grounded and calm because it’s not on me and our generation to solve everything, just to do the best we can so that those who come after us can continue to bend the moral arc of the universe toward justice. Practically speaking, it also means knowing the history of an issue you’re working on and using that history to inform your strategies.

Kotahitanga. Commonly translated as ‘unity’, but to me, this is about doing the work to bring people together across difference for a common purpose: the health and well-being of people, Papatūānuku, and all that we share the planet with.

Tiriti honouring. We recognise Māori as Tāngata Whenua and Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the Māori version of the Treaty text. If there is any conflict within a campaign between competing values. then Te Tiriti will have precedence in giving guidance on our decisions.

People-powered. We are of the people, by the people and for the people. Our power and legitimacy comes from the collective action of regular people. We operate on an ‘outside power theory of change’, because our members are outside the power structure. We don’t depend on being invited in by decision-makers. This approach puts power where it should be – in the hands of regular people.

Deep and digital listening. All of our work is built on a foundation of radical listening – our staff team spends many hours every week listening to everyday people in our country, learning what they care about, why they care, and what they want to see happen in our country. We do this in lots of ways, some as simple as reading and responding to hundreds of emails and thousands of Facebook comments every week, through to hosting focus group discussions on inequality around the country, public workshops/town hall meetings on the future of public broadcasting, and mass story gathering on experiences of the mental health system. All of this listening informs our campaigning by showing us what our community cares about and what is really going on in this country – beyond the headlines and outside of the major centres.

Collaborating effectively. We are strong believers in the power of collaboration to amplify impact and achieve progressive change. For 99% of our campaigns, we collaborate. This could be with values-aligned NGOs, community groups, academics, businesses, or passionate individuals.

There are more, but that’s probably enough for now. At ActionStation, we’re very big on what we call ‘values-led campaigning’.

A lot of your work involves mobilising people for change. Why is it important for all of us to be involved in politics?

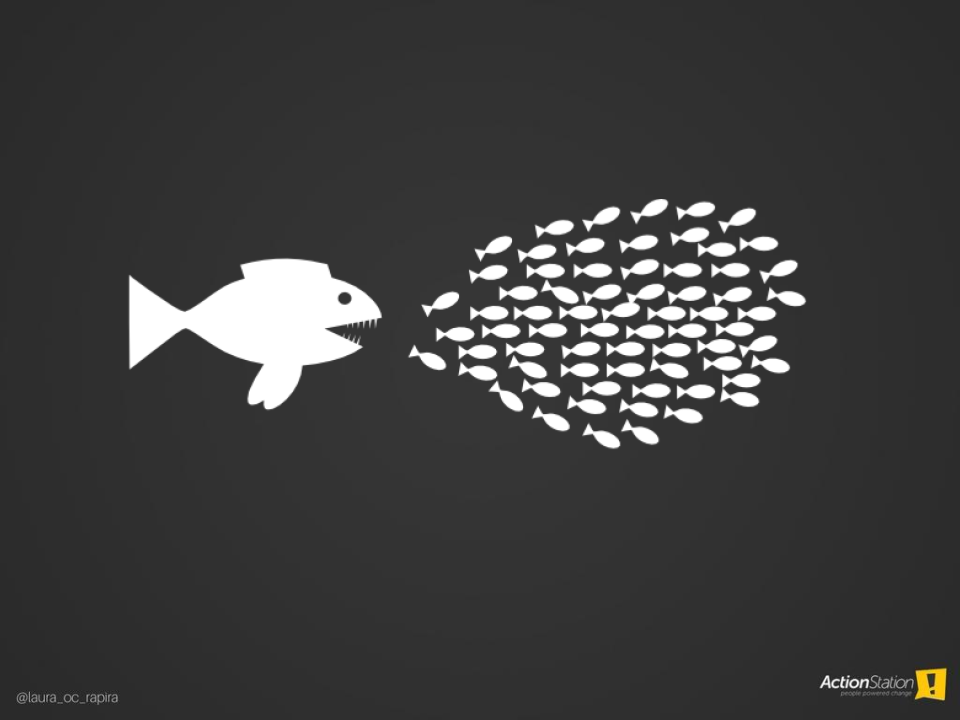

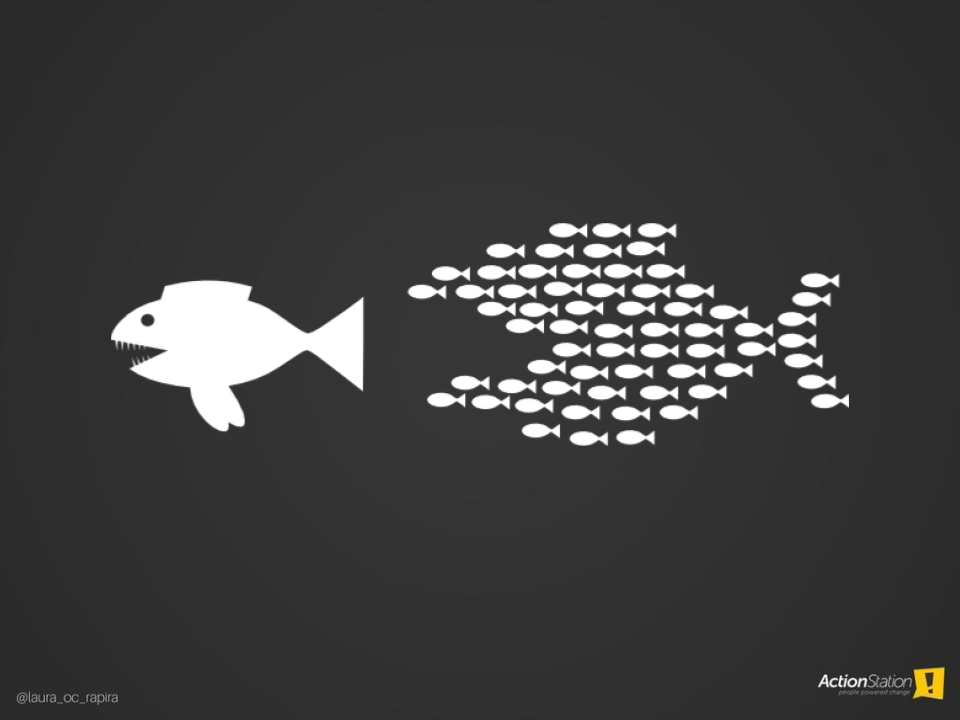

In my mahi, I get asked to do a lot of workshops and keynote presentations, and I almost always present these two images of organised fish:

The visual metaphor being that the big fish represents the world’s problems: climate breakdown, an unbalanced economy, enduring racism, and it can often feel like the big fish is winning. But if we coordinate ourselves and hundreds or even thousands of others, we can overcome those big problems together. All it takes for the world’s problems to persist is for us to do nothing, so all of us need to do something. And that ‘something’ doesn’t have to be running national campaigns like me – it could be making a meal for a neighbour or friend who is sick or has just had a baby. It could be voting for parties that align with your values, donating to worthy kaupapa, signing a petition for change, attending a rally, eating more plants and less meat, riding a bike or walking more often, being there for someone struggling with mental unwellness. It all helps.

When did you start thinking more about kai and why?

In high school, I was ‘adopted’ by a group of hippies who became my best friends. Most of them were vegetarian because they’d been raised that way, and they started to open my mind to the politics of kai. Then I watched the film Earthlings and I decided to be vegetarian and start volunteering for SAFE. I was 17 at the time.

I then tried to go vegan on and off for years and was finally able to make the commitment when I met my vegan partner who is very knowledgeable about kai and health and has taught me a lot. So I guess the key factor in all of that was relationships with people who were patient and kind enough to teach me. That and compelling (and devastating) documentaries like Earthlings.

Are there any connections between the changes you've made around kai and the exploration of your Māoritanga?

To be honest, it’s not something I’ve had a lot of time for sadly. I consider my contribution to exploring and developing my Māoritanga to be organising toward constitutional transformation at this time in my life. That said, one thing my partner and I have been doing more of is gardening and growing our own kai. We’ve been trying to learn more about the maramataka so that it can inform our gardening too.

Pania Newton recently said on Instagram that mahinga kai at Ihumātao has been a deliberate and peaceful act of resistance against the desecration of the whenua, the commercialisation of kai, and the oppression of culture. I love the idea of gardening as resistance, and it makes so much sense as that whenua, in particular, has always been a place that helps feed the masses.

How does veganism connect to your social justice mahi?

There are two of us in the ActionStation team who are vegan, and that has resulted in us collaborating more with animals rights organisations like SAFE and NZAVS which is awesome. All of the events that ActionStation organise provide plant-based kai only, and on the rare occasion we go out to a meal together as a team, we always support plant-based restaurants like The Botanist, Gorilla Kitchen, Boquita, or Mockingbird with our pūtea. For me, it’s about making small commitments that if hundreds or thousands of even just 10 people and organisations committed to as well would make a huge difference.

What are your hopes for the future of Aotearoa?

In 2017, the ActionStation community came together to create a shared vision for the future of Aotearoa New Zealand in 2040. We chose this date because it will be 200 years since Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed and a long enough time-frame to invite imaginative thinking. I consider my mahi (work) over the next 20 or so years to help bring this vision to life. Our vision is called Te Ira Tāngata: a People’s Agenda for Aotearoa and you can read it, and how we put it together, in full here.

Interviewed: November, 2019

Published: February, 2020

Published: February, 2020