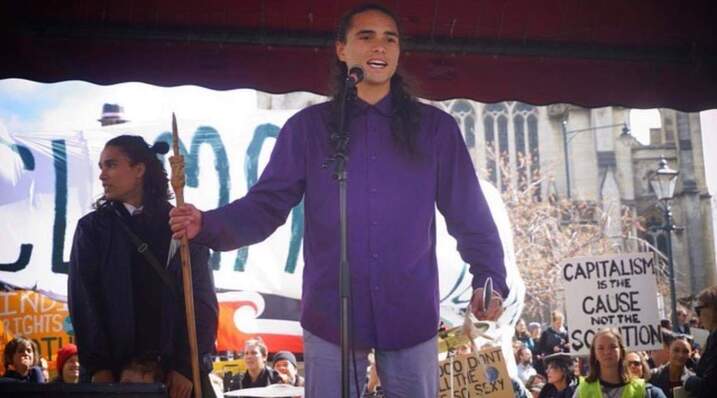

Poutama Crossman-Nixon

interview with Philip McKibbin

Poutama Crossman-Nixon (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi) teaches te reo Māori and waiata. He is passionate about te ao Māori and protecting our planet. He is a pāpā and lives in Ōtepoti with his whānau.

Tell me about your community work.

Kia ora.

It’s beautiful mahi, eh? So what I’m trying to do, really, is just thinking forward - thinking about the generations following. So I’ve started a whānau myself. I’ve got one two-year-old and another one on the way. In te ao Māori, we look at our whakapapa. A lot of people talk about whakapapa as history, but whakapapa, to me, talks about the whole picture. What is past is present. What happened in the past creates right now; what we do right now is creating our future. So that community work is all about creating a better future for our tamariki. So, working within my strengths in kura, helping bring te reo Māori to schools, encouraging that push. So hopefully we see bilingual units coming in. We have three in Dunedin at the moment, all in primary schools. So I’d love to see it transition over to intermediate and high school as well.

I have also been training for fighting - ring fighting, and that kind of stuff. I help teach in that gym, as well, that gym really gave a lot to me. So in that way, it’s not about the violence, it’s about the cultural reform in that gym, about that family, whakawhanaunga. Alongside all that mahi, I’ve set some other initiatives alongside in the marae, helping out that kaupapa, being a whaikōrero, learning mau rākau - so hopefully being a kaiwero for those kaupapa. And just other kaupapa to help flourish the ao there, set up a class that’s open for everyone. The main reason I set this up is observing that hidden barrier - not so hidden, actually - that really huge difficulty to learn te reo Māori. There’s a barrier if you’re not Māori, and even if you have light skin, to go and try learn Māori - man, it’s a horrible thing. Even being dark skinned and Māori going in as a fresh, new person, it’s difficult. But I just sympathise with all those of our people. So I’ve set up a class there to make it so it’s completely inclusive, cos that’s what te ao Māori should be, and I also set up a kapa haka thing - which is really about getting people to get out and sing some songs. So all of this, I’ve set it up to create a better culture in our community, thus Aotearoa, nē? - which is a part of the world.

What values guide you in your mahi?

I’d say there’s probably three pinnacle values which guide me. Which would be love, wisdom, and kotahitanga - oneness. So that’s really it. Within there, manaakitanga; within there, you’ve got tiakitanga. All of that stuff’s encompassed in those larger, core pillar values.

My grandparents - which is where I am now - they’ve taught me a lot about this. Being Christian, love and wisdom have been a big part of what they’ve taught me, and from that, forgiveness and all of these things. Why that’s important for me, and why that’s the pinnacle, is because I think it’s the only way forward, eh? I’d say love and wisdom are really two and the same thing. The more you love, the more wise you become; the more wise you become, the more you love. From love and wisdom comes oneness, and that’s what we’re trying to aim for globally, really. It’s just that counterforce to all of that bad stuff that’s happening in the world. It’s easy to see the bad; the solution is a much harder thing to see, and a less talked-about kaupapa.

A lot of what you do is about supporting others. Whose support sustains you?

Everyone that I’m supporting. The answer to that question is in this whakataukī - ehara taku toa nō te takitahi, engari nō te takitini. And that’s true, especially in my case. I was fortunate to be brought up from the start within a whānau that’s supportive. My grandparents have been here every Sunday of my life. So, really, that’s been a big privilege. All of the people that have supported me within the community, that’s where I draw my strength, and I think, even to this day, everyone else is the reason why I do my mahi - my whānau. I wouldn’t be doing it if I didn’t have those relationships. The only reason that pushes me is cos I love everyone that I’m actually helping out.

I see it as a picture like this: it always starts with the relationship we have with ourselves, and then from ourselves out to our closest members of our family - so, our direct family. That might be, now, my partner and our kids. And from there, our closer family - your parents, or whatever that is to you, your best friends perhaps. And then, to the more extended family, your extended friends, your community, and so on. And you actually love all those people, in different degrees. That’s where I draw my strength from, and that’s where I learn everything. I’d be an arrogant person to be claiming that all that I have now is because of me, nē? It’s everyone else.

Something you and I have in common is that we're both passionate about te reo Māori. Anō nei he rongoā te reo Māori, nē? Mā te reo, ka ora ai tō tātou ao Māori, ā, mā te ahurea Māori, ka ora ai ngā whānau Māori. How do you make te reo rangatira part of your everyday life?

Mai i te kōrero, bro. Mai i te kōrero. It’s simply said. Just speaking as much as I can wherever I can. Because there’s not much speakers down here, down South. So every opportunity I have with a speaker, I speak to. But when I don’t, I just speak to myself in my own head, and I only write in Māori. Whatever I do, I only do in Māori, when I can. This is actually advice I’d give to any learner of the language, is change your way of thinking from te reo Pākehā, or te reo Ingarangi, to te reo Māori. For me, my son’s a good help for that, and my dog. We all go for walks, and I only speak Māori to them. My partner’s learning, so I speak as much Māori to her as I can without annoying her, you know? (laughs) So it’s simply summed up as mai i te kōrero: trying to speak and finding any opportunity to speak, and that’s really the only way to really understand the language and how it applies to the world around us.

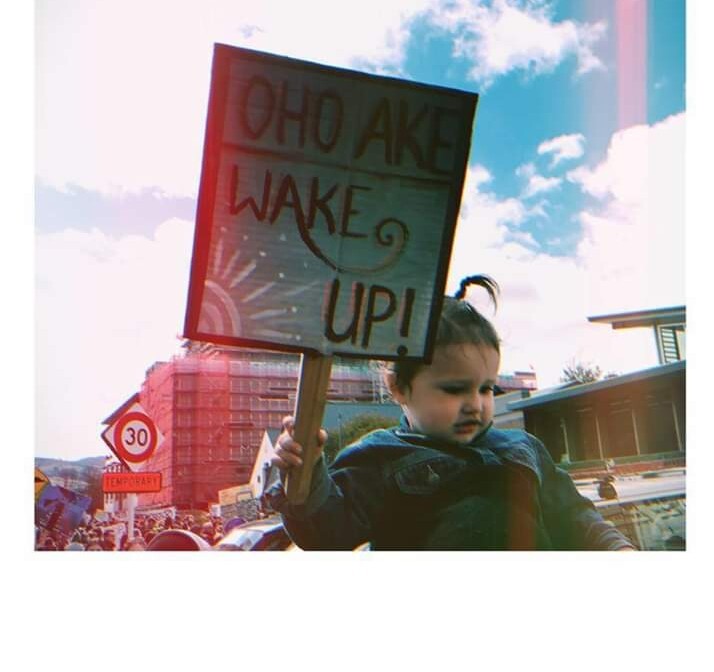

I hear you've been involved in climate action recently. Why is this important to you?

Kaitiakitanga. A really important value that I’ve been brought up with, through te ao Māori, and through kura, and through my kaumātua. Something that really has hit home for me, and really driven me to go towards being vegan has been driving through to Christchurch and seeing these big stretches of land, and just not seeing one ounce of ngahere. I used to drive through there and quite often just cry, you know, because it really hurts. Our country, Aotearoa, man, is the most beautiful paradise in the world, and it’s just been butchered - and butchered for suffering. You know, what we’ve butchered it for is no good, and it sucks as well, on top of that. The sustainable fight is for our country, but a lot of the time it’s not just for that, it’s for Papatūānuku, and the future as well. I could never kill anything. I remember one time where I went fishing with mum, and we caught a fish - thought it was a cool idea when I’d do it - caught the fish, it was thrashing, and we didn’t know what to do with it. Mum’s freaking out, I’m freaking out. I had to kill it to put it out of it’s suffering, and it really hurt - I was bawling my eyes out. I’ve always loved nature. I have a profound love for nature. It only occurred to me when I was looking at the food on my table, then I went, ‘Man, I’ve gotta make some changes.’ That’s why.

What changes have you made around kai to live in better relationship with Papatūānuku?

|

I just crack up - a good friend of ours, Mark, he always said he’s a ‘vague-an’, a vaguely vegan. We have a few naughty treats every now and then. And that’s kind of where I am now, really pushing and trying, really striving to be vegan, but my biggest problem is my addiction to sugar. Someone will have a chocolate, and I’ll be like, ‘Aw, no, I can’t eat that.’ But then I give in every now and then. But I’ve stopped buying it, so what I have done is heading toward vegan - completely vegan. I don’t eat meat, no meat at all. I’ll never eat meat again. And I just feel a lot better for it. Me and my partner, we’re working towards a totally vegan diet.

|

I heard this kōrero, I don’t know how true it is, but from someone at work who worked for a company, which said, for every one person that goes vegan, it stops the production of 700 animals, or something like that, all up. And I was like, ‘Man!’ That’s one person, eh? You have 10 people who do that, that’s 7,000. So for me, just reducing wherever I can, and not beating ourselves up about it, cos that gets us nowhere as well. That doesn’t mean we don’t push ourselves and give ourselves a little slap on the back every now and then - but yeah, just reducing the amount of impact I have, and trying to be a better conscious consumer.

You have a son, and another child on the way. Have you thought about veganism, or plant-based kai, with them?

Totally! With my son, I try to have him be vegan, as much as I can. Of course, he’ll have a little treat every now and then. But I look at the way I was brought up, and the kai I had, and I would have been a lot healthier if we weren’t in poverty, we would have had these diets. The way I see it, my growth has been stunted, because I lived off bread and meat for a big period of my life there, and just a lot of bad choices as well with my kai. So for my son, I can already see that growth in him. He’s strong as, because we’re really conscious of the food he consumes is what’s going to facilitate his tinana and his growth, so we’re really conscious for him. He might be annoyed every now and then when he wants to have a snack, but he’s going to be thanking us when he’s older. So we really want to adopt a vegan diet, specifically - because we don’t want to be hypocrites. ‘You can’t eat that, but we’re gonna have this.’ But, the tinana is a part of the whare tapa whā, nē? And what we eat creates our āhua – just the same, what we learn is the kai of the hinengaro, and we’ve got to be very conscious of what we’re consuming there - so the kai that we eat on our plates is also a reflection of how we think, as well. Just trying to be conscious every day is the aim.

Do you see other positive impacts that come with your lifestyle?

I think it’s all positives. You know, as far as it concerns my body, I’ve just got a lot more energy, I’m fitter, I think clearer. I notice if I eat that stuff that I shouldn’t, if it’s dairy, I get clogged up, and slower, I get headaches and a runny nose. Just by eating well and eating fresh kai and balancing it out well - I get boundless energy. As fit as could be. And how that relates to everyone else is because if I’m in a better space, not cranky, not whingey, then I can do more for our people. Also, within that, how that helps everyone else is, we gently prod them along to be vegan by being vegan. With us, it’s not force. So when we have stuff, they’ll come to the kaupapa. We don’t say, ‘It’s only vegetarian.’ You can bring your kai. But most often people only bring vegetarian and vegan foods - not because they feel like they have to, but out of respect, and because they’re starting to realise that it’s actually yum. It’s delicious.

That’s probably one of my favourite benefits, is that being vegan, I’ve eaten the best food I’ve ever eaten in my life. The more I learn – the yummier the kai. Man, vegan food is delicious. People just assume that, ‘Aw, no meat. Must be gross.’ And then they try it, and they’re like, ‘Oh, man, that’s delicious.’ It’s always fun telling people, ‘No meat in that!’ (laughs) So I think it’s a no-brainer, for the planet, for the community, for hauora.

I think, specifically here in Aotearoa, te ao Māori has been probably the biggest, most important thing for me, and for the people I’m around. People have these different kōrero around Māori, which is something I’d like to talk about, what ‘Māori’ really is to me. If you look at our cultural structure, it’s never been just about blood. Whakapapa’s been important, but ‘te ao Māori’ is quite a loose term. And people assume it comes from the top here, and filters down, but the very nature of te ao Māori is that it comes from the individual, the hapū, the whānau, and so on, and eventually you get here, Māori, and we’ll say you’re Māori. So what I talk about being Māori is not by blood. Being Māori by blood means you have a responsibility to uphold and to push forward our ao and facilitate it for others to be a part of, like our tīpuna did. So being Māori, to me, you need to be totally for your people, your whānau and your hapū. Every hapū has their own uniqueness, unique Māoritanga. Not everyone has to be Māori by blood to be incorporated into the hapū. That’s the beauty of it. The door should be open. I’ll finish with this whakataukī - ko te reo te manawapā o te Māori. Kia ora!

Interviewed: November, 2019

Published: March, 2020

Published: March, 2020