Te Haunui Tuna

interview with Philip McKibbin

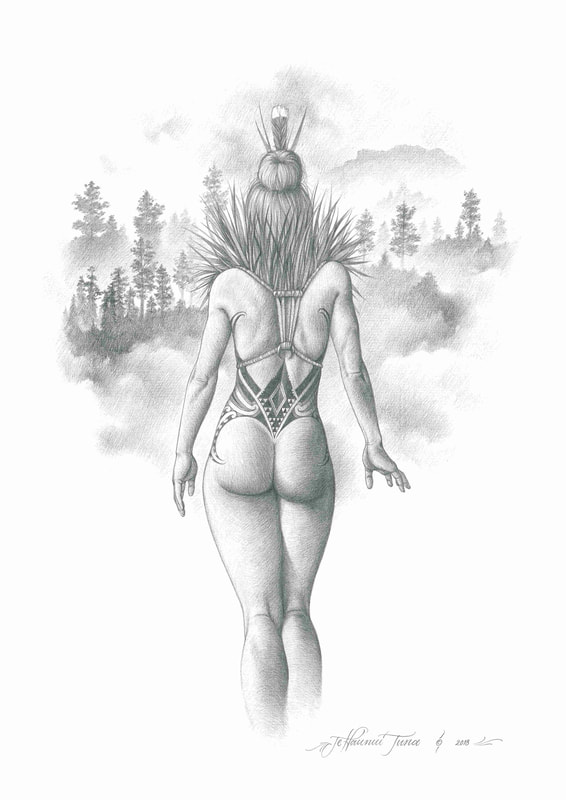

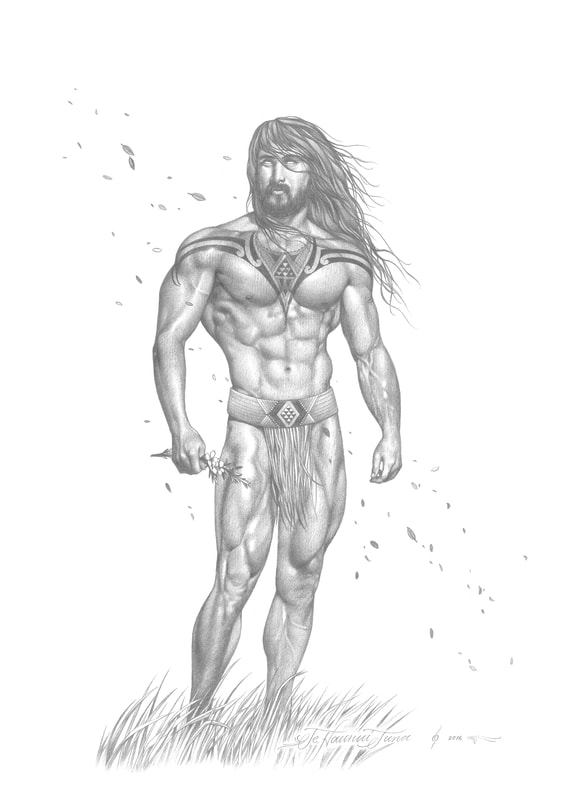

Te Haunui Tuna (Ngāi Tūhoe) is an artist. He grew up in Waimana, and he lives with his partner in Whakatāne. His work is inspired by his Māori heritage – it often depicts atua Māori, and frequently represents whakapapa. He enjoys tattooing, painting, sculpting, and drawing. He also runs Moko for Moko's, which creates a fun and safe space for tamariki to experience traditional Māori art through temporary tā moko.

https://www.tehaunuiart.com/

https://www.facebook.com/tehaunuiart/

https://www.instagram.com/tehaunuiart/

https://mokoformokos.com/

https://www.facebook.com/tehaunuiart/

https://www.instagram.com/tehaunuiart/

https://mokoformokos.com/

|

In what ways did your upbringing shape the way you understand the world?

This is a question I’ve thought about quite a bit. I’ve got three older siblings, two younger siblings – but two of my older siblings both passed away before I was born. So we grew up in a house that was quite busy, cos it was my older brother, me, my younger brother, and then our younger sister. Our parents let us be who we are. I think that was probably the biggest thing. Our parents didn’t try to make us a certain way. The only way they tried to make us was to make us be nice people, and make us humble people – no matter how well you do, or how good you get at whatever it is you do, to always remain humble, to never think you’re better than other people.

|

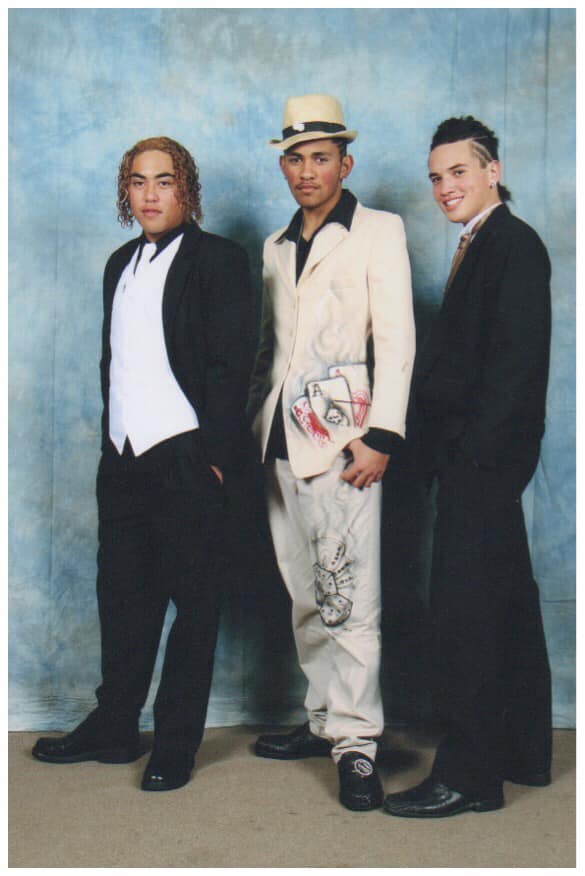

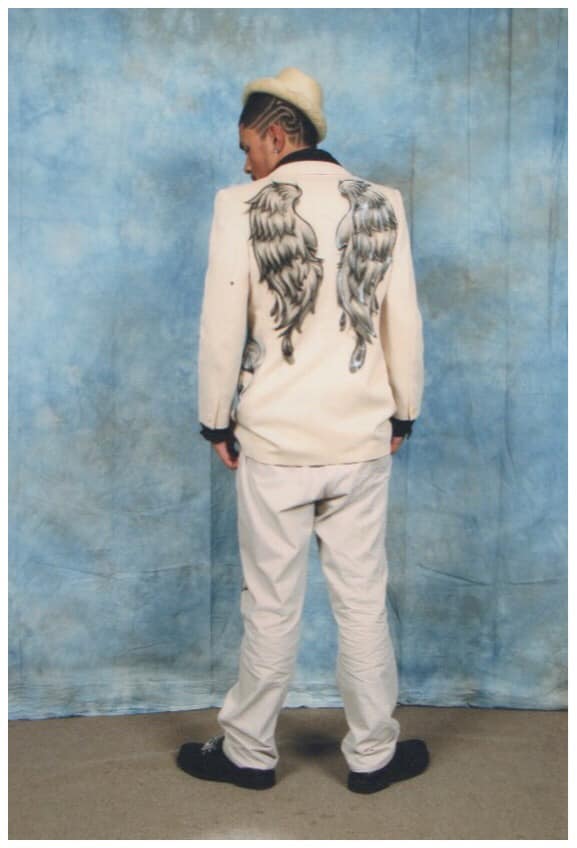

I think that sort of upbringing, just letting us try different things… Cos I’ve definitely seen it with a lot of people, where it’s obvious they want to do art, for example, but their parents don’t see a career out of art, so they make them do sports, or they make them do science, or something else. But our parents, they were just – as long as, whatever we did, we gave it 100% – they were alright with it. All you had to do was look at me, for example – if you looked at old photos of me, just the way I dressed, I dressed pretty funky. I was always keen to be different. That has shaped the way I look at the world, and more specifically, my dad, cos my dad, he’s an out-of-the-box thinker, and he was my art teacher growing up, as well. He got me into fantasy art, and comic book art, things like that, as a kid. Even when I was doing that sort of stuff, he would always make me think about, ‘What else aren’t you seeing?’ And that made me try to always think about what’s not being seen, what’s not being said.

I realise, now, that that made me super open-minded, and it made me lead my life in a way that’s guided by how I feel instead of how someone else makes me feel about something. So, for example, being vegan – logically, I know it’s right, but it also feels right, as well. So I try to lead my life like that now, doing things that I know feel right to me. And also understanding that, you know, I’m just a person; I have flawed, subjective views, whether I like to admit it or not. But I try to remain as objective as I can, and I’m always open to adapting if something else can be proven better than how I think I lead my life. So yeah, in a nutshell, just my parents letting my siblings and I be who we are, and letting us be curious, and be different – that’s made me look at the world the way I look at it.

How does your love for te ao Māori find expression in your art?

I’m super grateful to grow up the way we grew up. We grew up doing kapa haka our whole lives; we grew up on our marae; and we were raised by our nan as well. She lives up the bush, and the marae’s just up the river from her house, so we lived up there, pretty much, as well. It’s all I knew, and I didn’t realise it until I got a bit older, but as a kid – cos that was all I knew, I didn’t think that much of it. I didn’t think it was that special, you know? Like, growing up in N.Z. for example, seeing rolling hills, and seeing trees, and seeing grass, and all that, I didn’t think it was that special until we went overseas and went to Singapore and didn’t see any grass. We were like, ‘Oh, geez!’ So, yeah, just growing up on my marae and learning about a lot of our Māori stories. I didn’t learn them in super detail. The reason they were fascinating to me is cos they sounded like comics, and they sounded like movies. And all the work that I do now is literally all influenced by being Māori, and my mission now in life – and, like I said, it’s always open to be changed and to be pivoted along the pathway – but my mission now is to use Māori stories, and doing it through visual storytelling, whether that be moko, or illustration, or film, eventually, and using art as a vehicle to share Māori stories in order to inspire Māori people. Cos we all know people who are down and out – like me, for example, I have a lot of whānau who are in gangs and stuff, who I know are super talented people, but ain’t living up to their potential because of the environment they live in. I believe if I can do all of these things that I want to do, and inspire them, it will help them to realise their own potential. I know for me, I’m more inspired by somebody that I can relate to, and I think that works for everybody. People are inspired by people they can relate to, cos if they can relate to them, then they can see themselves as that person, or see themselves achieving greatness. So, yeah, using Māori stories and my upbringing definitely did that, cos I was brought up with Māori stories. It’s exciting for me, I enjoy doing it, and the fact that it can do good as well is just the cherry on top.

When did you first start thinking about making changes to what you eat?

I first went vegetarian in 2015 – it was around August, 2015. My partner was already vegetarian, March that year. She didn’t force me. I was, like, the last person I would have thought would be vegan. (chuckles) And I already had a vegan mate, as well, in Hamilton, and he was a mate that I tattooed with – and I remember what he would eat, and I’d just be, ‘Nah! I can’t eat that. I have to have meat.’ That’s what everyone says. Then I watched a video – like a lot of people – I watched just one video, and it wasn’t, like, a video of slaughterhouses or anything like that, but it was just this old dude. He was at a conference or something, and he was talking about the impacts on the environment. Everything he was saying just resonated with where I was at that point, and everything made sense. And the things that he said, I thought about and applied to New Zealand, and to my upbringing – cos I lived across the road from a farm. I thought about that, and I thought about all the paddocks that I ever grew up around, and that I’d ever seen, are all for cattle. And I was like, ‘Man!’ That made sense. I watched just one video, and I thought, ‘Yeah, I think I could go vegetarian,’ and went vegetarian. And I would say that was probably harder than when I went vegan – even though vegan’s obviously harder – it was just cos it was a huge shock for what I was used to my whole life.

And then, after that, 2016, the next year, just before Easter, I watched The Cove, and just seeing those dolphins being killed… I grew up just loving kittens and loving cats, and I remember whenever kittens would die, I would just cry as a kid. And watching The Cove just reminded me of that time, and I was like, ‘Man, what makes dolphins dying different to cows dying so I could eat it?’ And yeah, I decided then. I was like, ‘Should we be vegan?’ to my partner, and she was like, ‘Yup.’ And yeah, Easter 2016 – been vegan since then. It was one of the best decisions of my life.

Tell me about your journey with veganism.

The hardest days are definitely the early days, because you go into it only knowing what you eat, which is majority stuff that you can’t eat as vegan. Yeah, that’d be the hardest part, just figuring out what to eat. When we went vegan, we were eating chickpea salads, and roast veggies, and hot chips. (laughs) I remember thinking, ‘Man. This sucks. There’s gotta be better stuff than this.’ But we got used to it – you get used to going to the supermarket and just choosing certain things. Definitely some of the harder things is when you go out to eat with friends and family, especially here in Whakatāne – there’s not many places you can go and have a good vegan option. Definitely getting more now, but you get used to either eating beforehand, or eating hot chips, or just drinking and waiting until you go somewhere else afterwards. I did kapa haka in the summertime for kapa haka competitions in February, and that was – it wasn’t hard, but it was definitely a challenge, because you’ll always just get 21 questions every practice, every lunch time, every dinner time. And, you know, you get eight people who are genuinely curious, and then you get two people who are just cheeky. (laughs) They say every cheeky comment under the sun. But my whole life has built me up to just be okay with who and how I am, and that made me alright with it.

But challenges, you’re always gonna get people saying ignorant things to you, and for me, I’ve always tried to be empathetic, cos I understand that was me as well before. I haven’t always been vegan, so I just try to answer it as best as I can whenever they do ask those sort of questions. In saying that, though, from 2016 to now, 2019 – man, there are way more options now for vegans. We have options of vegan ice cream now at the supermarket, it’s not just one Coconut Island ice cream, you know? (laughs) I went to Hell’s pizza maybe a month ago, and they had, like, six vegan pizza options – which is insane – and the one that I got was delicious. So yeah, challenges are facing people in your circles, and going out to eat – things like that. But yeah, it’s definitely getting easier, cos we hear about vegan options all the time. I think people are more… they’re used to it now. People ain’t like, ‘What the hell’s vegan?’ People have heard of vegan, they know vegan people – some of them even adopt one vegan meal a week, which is awesome. So yeah, that’s probably it.

In what ways does veganism connect to your Māori values?

I think that’s a good question. For me, being Māori is all about connection, you know what I mean? Hence why whenever we meet people, we ask about people’s whakapapa, we ask where they come from, who they’re related to, so we can make connections. We also do that with our environment, as well. I think for me, being connected to the environment, and being connected to animals, it’s helped me realise that we’re not more, or we’re not separate from our surroundings, but we are just another cog in that whole collective machine, if you can call it that. And when I think about it like that – when I think about our connection to our environment and to the animals – yeah, I think about us all on the same level. The fact that we don’t have to eat animals makes me realise, I shouldn’t, and I don’t want to if there’s an option not to. We can thrive and survive off eating plants, just like a lot of animals do in the world. It’s about connection and just realising that we are not more than our environment or the animals that are in that environment. We’re just one part of it.

For me, I think about my place in the universe – this is thinking a bit different, my upbringing has made me think like this – and I often think about a life with purpose and a life of meaning; and then sometimes I think about oblivion, and I think about the fact that there will be one point in time where every memory of now ceases to exist; and I think about, for me, what I want to do while I’m here, while I’m alive, is to enjoy life as much as I can, and help other people and other animals enjoy it as much as they can, as well, and to cause as less harm as I can while I am here. Being Māori, for me, the relationship between those two things is connection, just being connected and thinking more deeply about our connection to everything around us.

Has your veganism encouraged others to make changes around kai?

Yeah, definitely! So, my best mate, Raniera Rewiri – I was the reason that he was curious about it in the first place. At the end of 2016, he decided that his challenge for 2017 was he’d do one challenge every single month for 2017. Me and him, we’d already bought tickets to Tony Robbins, which was in May 2017. I was already vegan by then, and we were gonna fly over together, so he said, ‘What I’ll do to make our trip over to Australia easier’ – it was in the Gold Coast, by the way – ‘is I’ll go vegetarian for April, and I’ll do my research so I can get used to it, and then I’ll go vegan for May, so when we’re in Australia together, we can just eat the same thing, just to make the whole trip easier.’ And he was only curious about that cos I was vegan already. And knowing the person who he is – he’s a person who likes to do things 100% or not at all – I knew that when he would do it for a month, it wasn’t gonna be for one month, he was gonna do it for the rest of his life. And sure enough, since going vegan, his whole life has changed. He’s got a vegan food business, which is literally serving vegan kai to people and sharing a message that’s connected to what you eat and being Māori, and everything that comes with those things.

My sister, she went vegetarian for a bit, cos my partner and I were vegetarian. I think she’s gonna go vegan cos of the stuff that’s happened in the Amazon. I can tell that her calling, and the way that hits home for her, is things to do with the environment.

I think people around us are more open to it. I remember when we first went vegan, people wouldn’t even try vegan food – but now they actually try it, and we get to the point where we have to tell people not to eat it cos there’ll be nothing left for us! (laughs) ‘We can’t eat what you can eat. We can only eat this, so save us some, please.’ I’ve gotten messages from strangers – people that I don’t know – who have been curious about veganism. Seeing what we eat has helped them to give it a try, or at least give one meal a try, which is awesome. For me, whenever people ask questions about it, or people are curious about it – like, genuinely curious about giving it a try – I just tell them all to do it in their stride, to do it however you can do it sustainably. If it means removing milk, and then, when you get used to that, removing one other thing, then do it that way. If you’re a person who works going cold turkey, and you have to go straight vegan straightaway, then do that. But yeah, I never try and put pressure on anyone to do it exactly the same way I did it, because it may not work. And for me, I know sustainability is the way, instead of people just giving it a try for one week and then going back to the way things were. Yeah, so it’s pretty cool that people have been more genuinely curious about veganism since I’ve gone vegan.

When we choose to do things differently, it can often be difficult. Have you discovered any successful strategies for carrying your veganism with you in Māori spaces?

I think it just comes down to the type of person that you are. If you’re a person who over-values what people think of you, you’re probably going to have a hard time. If you’re a person who is fine with who they are, who is fine with going against the grain, you’re gonna be sweet. If anything, you’re gonna relish it. (chuckles) Cos you’re definitely gonna get attention if you go to the marae and you say, ‘Oh, I don’t eat meat,’ or, ‘I’m vegan.’ A lot of your whānau – especially the older whānau – they just cannot believe it. They cannot believe it. So, put simply, it comes down to the type of person that you are, really – and if you’re doing it for reasons you believe in. If you’re doing it for reasons that you don’t believe in, it’s probably going to be a bit easier to shake you, you know what I mean? If it’s something that you fully believe in, 100%, it’s pretty easy.

An example I give to people when they ask about how I don’t eat meat, I just say, ‘It’s just like if you think about other cultures where they eat animals that you don’t eat – if they eat horses, or they eat dogs. For them, it’s normal, but for you it’s normal not to eat it, so you won’t eat it. That’s what it’s like for me not to eat meat in general. It’s not normal for me anymore, so it’s not hard for me to say, “No, thank you.”’ And then when I tell people that, they realise, ‘Oh, yeah, true!’ When we grow up eating what we eat, we get used to eating that, and we think it’s the norm. Anything out of that norm seems strange, even if it’s someone else’s norm. For example, eating beef. In India, they don’t eat beef. For us – especially for Māori people – it’s always beef. The fact that you go to a country where there’s cows walking across the roads everywhere and they don’t eat beef – it’s so strange to them, it’s so strange to our people. I like to use those examples to help people think from somebody else’s point of view. And yeah, nine times out of 10, that makes people think, ‘Oh, yeah, that makes sense.’

What's your favourite vegan kai? Not chickpea salad, I’m guessing?

Definitely no kind of salad! (laughs) I’ve never been a salad person. I’ll eat a salad, but I’ve never, ever gone out of my way to have a salad. (laughs) My favourite vegan kai? Man, this is a big one. Right now, it’s hard to say one that stands out, but I’d say right now it’d probably be vegan boil up – and funnily enough, we’re having it today, so I’m stoked. It’s just doughboys, watercress, potatoes, kūmara, pumpkin, kamokamo during summertime, and just some bread, Olivani, and some tomato sauce. Sorted! And something I love about that sort of kai is it’s real simple, it’s a big dish – like, I grew up with my siblings, and we ate big dishes of things, so whenever we ate something, there was always enough for lunch the next day. So I like eating food where it’s made in big portions – big pots or big trays – things that I can eat and then have another feed an hour later. (laughs) So yeah, at the moment, it’ll be vegan boil up. And a lot of people who ain’t vegan, who eat boil up, will be like, ‘What the hell? How does that even work?’ (chuckles) I’ve told plenty of people that. And they’re like, ‘That’s just boiled veggies.’ (laughs) It’s like, ‘Well, these boiled veggies taste damn good.’

I would just say to all the people reading this, if you’re curious about veganism, go down the path, ask more questions, and be okay with being who you are, cos I think if you’re okay with that, you’re okay to be different from everyone else around you. I think that’s a big thing that you can apply to your whole life – to be okay with being who you are. You know who you are, if you’re honest with yourself. Who you are is the person who you were as a kid, pretty much, a kid that wasn’t conditioned by the world yet. So yeah, just be who you are, and find out who you are if you don’t know.

Interviewed: October, 2019

Published: December, 2019

Published: December, 2019